Bedouin Poetry

Chapter VI

[59] Contemporary Arab Poetry, Bedouin and Urban

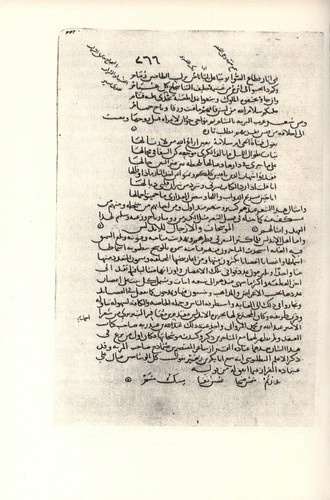

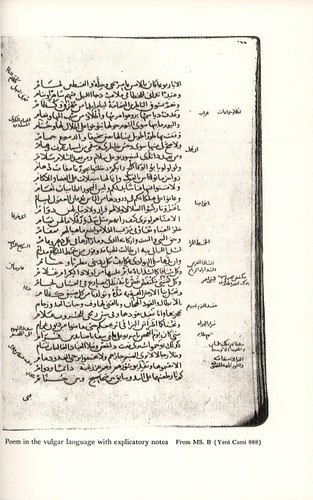

Poem in the Vulgar Language

Abstract: The Journey of the Hilâl to the Maghrib

"Another such poem deals with the journey of (the Hilâl) to the Maghrib and how they took it away from the Zanâtah. (It runs:)

What a good friend have I lost in Ibn Hâshim!

(But) what men before me have lost ood friends!

He and I had a proud (quarrel) between ourselves,

And he defeated me with an argument whose force did not escape me.

I remained (dumbfounded), as if (the argument) had been pure and

Strong wine, which renders powerless those who gulp it down.

Or (I could be compared) with a gray-haired woman who dies consumed by grief

In a strange country, driven out from her tribe,

Who had come upon hard times and finally was rejected

And had to live among Arabs who disregarded their guest.

Like (her), I am as the result of humiliating experience

Complaining about my soul, which has been killed by boredom.

I ordered my people to depart, and in the morning

They firmly fastened the packsaddles to the backs of their mounts.

For seven days, our tents remained folded,

And the Bedouin did not erect tent poles to set them up,

Spending all the time upon the humps of hills parallel to each other." (op. cit., ibid., Vol. III, pp. 419-420)