Early History, Sixth Century B.C. to Sixth Century A.D.

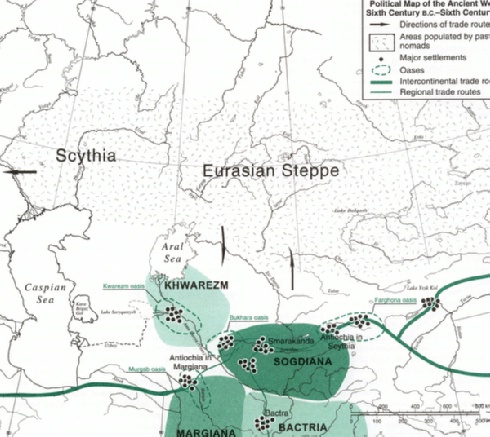

Map 6: Political Map of the Ancient World

The place of Central Asia in ancient world history is very difficult to define (Adshead 1993). However, existing evidence suggests that during the eleventh to seventh centuries B.C. the population of Central Asia was already engaged in various forms of crop cultivation and animal husbandry. Moreover, there was a division of labor into two large groups. One was represented by settlers who cultivated fertile soil in numerous oases on and around the Zeravshan, Murgab and Amu Darya (Oxus in ancient Greek chronicles) rivers and their tributaries. As early as this period, Central Asians introduced irrigation techniques that helped to establish and maintain relative prosperity in their lands. The other group was represented by the nomadic and seminomadic population of the vast steppe to the north of the Syr Darya River. During these centuries these peoples domesticated and actively traded their animals (horses, camels, sheep, goats and bulls) with settled populations in exchange for grain, weapons, metal work and manufactured goods.

Between the eighth and sixth centuries B.C. the early ancient states and protostates had emerged in the Transoxiana (the area between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers), the earliest appearing at the Farghona, Murgab, Bukhara, Khwarezm and other oases. From the sixth to the third centuries B.C. Central Asian peoples had established several principle urban centers on sites close to present-day Samarqand (in Uzbekistan), Balkh (in Afghanistan), Merv (in Turkmenistan), Khojand (in Tajikistan) and many other cities. Some of the cities were quite large, at times supporting populations in the tens of thousands. Other cities and towns were relatively small, as their citizens were exclusively engaged in subsistence and small-scale commercial agriculture and harter trade.

These urban centers were in one way or another linked to the major world powers of the ancient era, as gold and jade originating from Central Asia were found in China and Persia. In the ancient era the Central Asians dealt with four great neighboring powers-Persia, China, Mediterranean states and Scythia-who would eventually play important roles in the history of Central Asia.

The early Persian states were situated in the neighborhood immediately to the south of the major Central Asian cities. From early times they were linked to some of the original Central Asian city-states through intensive trade and cultural exchange. The Persian rulers regularly launched relatively minor and at times considerably larger wars and campaigns to the north in order to expand their direct and indirect control over this area. For example, in 530 B.C. the Persian King Cyrus II the Great (ca. 590-530 B.C.) campaigned in Central Asia but was defeated by an army led by Queen Tomiris. However, Darius II returned a decade later with a larger army and conquered Central Asia, turning Bactria, Parthia, Khwarezm, Ariana and Sogdiana into Persian satrapies and recruiting Central Asian cavalry into the Royal Persian army.

The Mediterranean or western powers were situated far to the west. About 2,000 miles (3,300 kilometers) separated the major Central Asian cities from the early Greek city-states in the Mediterranean. Yet the Greeks expanded their numerous trade outposts and colonies in all directions, and evidence suggest that they reached as far east as present-day Iran, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan. Herodotus (ca.484-425 B.C., the "father of history"), indicates that the Greeks knew about the development of the Persian and Scythian worlds (modern Central Asia) and their traders, spies, missionaries, scholars and adventurers regularly reached some parts of Central Asia (Herodotus 1963).

Major ancient Chinese cultural and political centers were between 2,000 and 2,400 miles (3,300 and 3,900 kilometers) east of Central Asia. They were separated not only by great distances, but also by wild and impenetrable deserts, steppe and mountains populated by powerful nomadic and seminomadic tribes. Many adventurers, traders and scholars traveled to and from nonetheless, and by the sixth century B.C. the Chinese already had a relatively clear cultural and political portrait of the Central Asian lands. The ancient Chinese historian Sima Qian (ca.145-85 B.C.) was able to describe land to the west of China with considerable accuracy using earlier chronicles and reports.

The powerful though unstable Scythian tribal confederations of the vast Eurasian steppe formed an independent political force that played an important role in the history of the Central Asian city-states. Scythian political and military activities were especially visible when capable and ambitious leaders emerged, bringing formidable forces under their control. At the same time they contributed immensely to the economic development of Central Asia as they supplied valuable goods for the region and for international trade. Ancient historical chronicles suggest that the Scythians were engaged with the Persians and Greeks both militarily and commercially.

(ibid., Map 6: Political Map of the Ancient World)